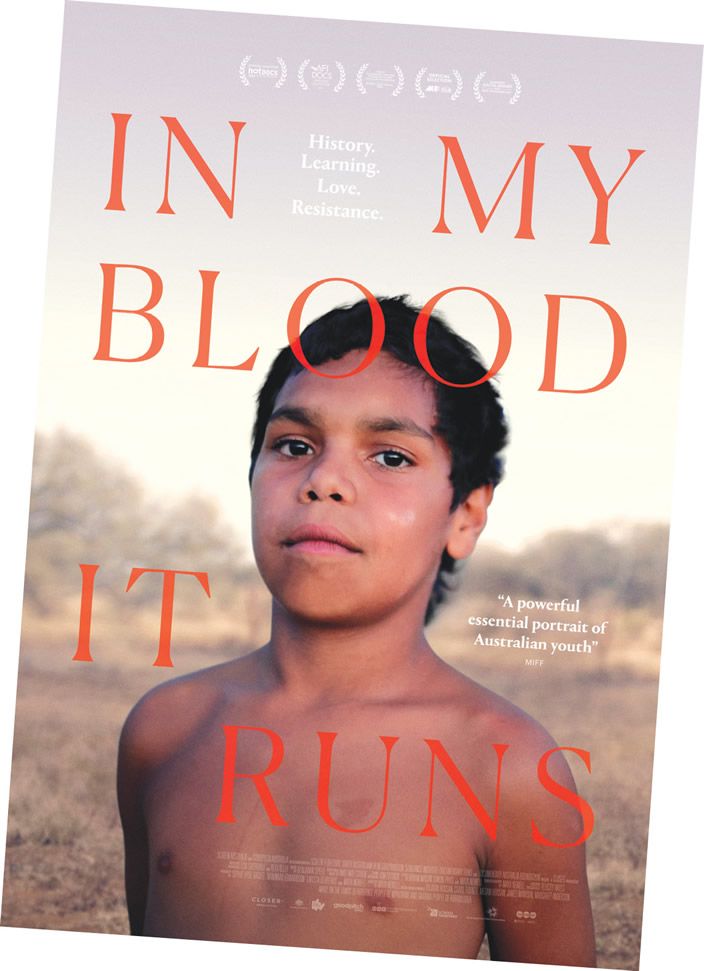

Meet Dujuan, a captivating young Aboriginal boy who, despite great challenges, has plenty to teach all of us. Journalist Angus Hoy reviews a recently premiered documentary.

In my blood it runs is an observational documentary following an Arrernte and Garrwa Aboriginal family in Alice Springs. Focusing on 10 year old Dujuan Hoosan and his family, the film skilfully demonstrates the challenges Aboriginal communities face in navigating education and social systems still deeply informed by Australia’s colonial history.

The documentary, directed by Australian Maya Newell – who’s previous work, Gayby Baby, was critically acclaimed for its depiction of the daily lives of children of single-sex parents – credits Dujuan as co-cinematographer and members of his family as collaborating directors.

Set in Mparntwe (Alice Springs), Sandy Bore Homeland and the Borroloola community in the Northern Territory, the film is shot in an intimate and unhurried vérité style that nevertheless bristles with the injustices of impoverished and dispossessed communities, facing up against institutionalised racism within systems of education and juvenile justice in Australia. Produced over three and a half years, during this time Dujuan found himself struggling with home life, school and interactions with police and social services.

In 2019, Dujuan was the youngest person ever to speak to the United Nations Human Rights Council, where he spoke about the high incarceration rates of Indigenous youth. He is shown in the film as continuing to learn about his culture and connection to his country through elders and family members; Dujuan is also encouraged to use his native languages – he is trilingual – and he is learning traditional healing and bush medicine practices.

Yet, we see that this sensitive and intelligent young person is “failing” in set curriculum subjects at school. His white teachers are dismissive of Aboriginal stories and spiritual beliefs while teaching a whitewashed version of colonial history. In one scene a teacher shows a book of Australian history from 1952, saying “this one isn’t a story, this is information – it’s fact”.

Dujuan becomes disengaged and frustrated by schooling, borne out in suffering grades, attendance and behaviour. His family is told that if his attendance doesn’t improve their social welfare payments will be cut off and that Dujuan could be taken by the state and placed in juvenile detention. After watching an ABC Four Corners investigation into Indigenous youth incarceration, Dujuan’s Aunty warns him that going to juvenile prison means “you’re only going to end up in two places: a jail cell or a coffin”.

The film artfully balances these crushingly heavy themes with slices of real hope and inspiration, and treads the line between polemic and observation with a nuance only possible thanks to the deep collaboration between the documentary’s creators and the communities who are its subjects. The film’s creators self-consciously describe it as not just a film, but also a campaign for change.

“The Arrernte and Garrwa families and communities behind the film have guided a multi-year impact campaign that dovetails with our film release,” they write. “You can support their solutions by backing their campaign focusing on three main goals: education, juvenile justice and racism.”