Few things are as divisive in education as the debate about different philosophies of teaching and learning, IEUA NSW/ACT Organiser Keith Heggart writes.

In recent years, and largely thanks to social media, such debates have expanded and, on occasion, become personal and acrimonious. Often these debates revolve around the efficacy of different modes of instruction – the debate about direct instruction compared to project based learning has been particularly heated – but they often also include discussions about how best to manage the behaviour of students.

In the United Kingdom, for example, the Michaela Community School was recently described as Britain’s strictest school due to its application of a ‘no excuses, zero tolerance’ approach to student behaviour.

More recently, there has been discussion about the behaviour of students in corridors. Ninestiles, a secondary school in Birmingham, has instituted a new rule that requires students to walk silently between classes. This has been put in place so that students can arrive at class in a quick and efficient manner, ready to begin their learning in a calm fashion. Students will be allowed to speak to each other – but only in designated areas at lunch or recess time. Students who fail to follow this new rule will receive a 20 minute detention for the first offence; repeated infractions will lead to an escalation of the school’s response.

Predictably, such an approach led to both outrage and support from educators and academics around the twittersphere. For example, Tom Bennett, a UK educationalist and government adviser, suggested that it was something of a storm in a teacup. Bennett suggested that this was “a column guzzling non story that chewed up social media for the first half of half term” (https://schoolsweek.co.uk/silent-corridors-whats-all-the-fuss-about/) and really, it wasn’t at all restrictive to expect students to be quiet at certain times. After all, Bennett argues, we do this when we ask students to read silently or listen to teachers at assembly.

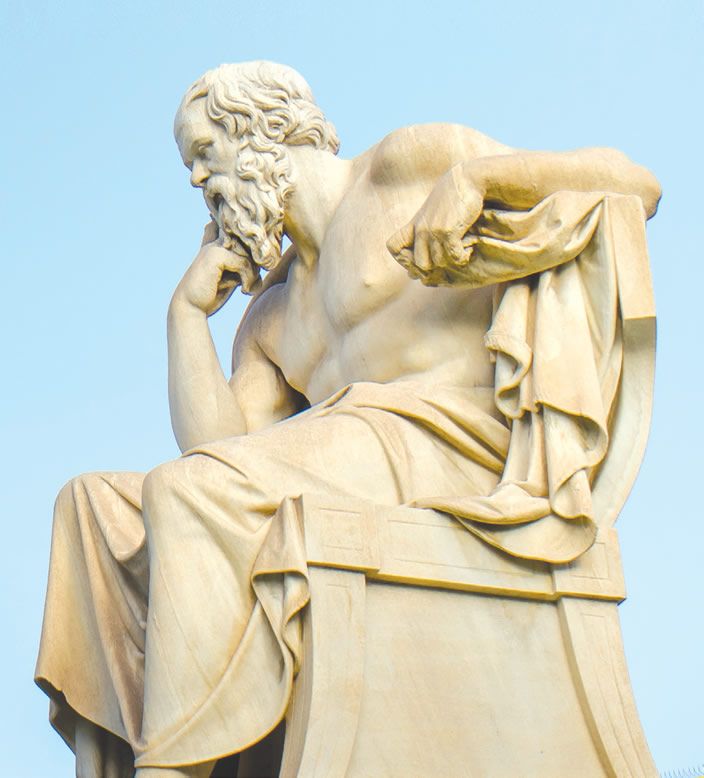

Other educators have suggested that such an approach is unnecessarily repressive and brings to mind images of Victorian era prisoners in hoods. Some educators, like Amber Kim, have suggested that such an approach does little to reduce educational inequity, especially for students from marginalised backgrounds. Instead, it assists in reproducing the status quo – which disadvantages those students and advantages a dominant group (https://amberkkim.wordpress.com/2015/03/28/silent-hallways-are-unjust-let-students-speak/). Others argue that it takes the joy and hope from schools and replaces it with a grudging level of compliance.

Regardless of your opinion about silent corridors, it is clear that this is another approach that some schools in the UK have adopted – for better or worse. One thing that is certain is that, like many other ideas before them, this idea will probably soon make the trip down under.