A 2007 Australian Bureau of Statistics survey found that 19% of 18-24 males had engaged in high risk (binge) drinking at least once a week. In 2005-6 more than 15,000 people aged 15-24 were hurt in a transport accident, with males twice as likely to get injured as females. In the 2007 National Drug Strategy Household Survey 23% of 15-24 year olds reported using illicit drugs in the previous

12 months.

The Writing’s on the Wall

Melville Council, which governs a suburb of Perth, has produced educational resources aimed at cutting down on risk-taking behaviour by its youth, hoping to prevent crime and expense for the Council, as well as keeping young people safer.

Some six years ago the Council produced Six Mates, stories for young men. More recently it made The Gathering, a DVD aimed at 15-18 year-olds about a party, which goes badly wrong. The resource aims to tackle binge drinking.

Its most recent effort, out last September, is called the Writing’s on the Wall (www.melvillecity.com.au/twotw), a script for high school students aimed at tackling graffiti tagging, but relevant to other risky behaviour.

Council Health and Wellbeing Coordinator Janet Armarego says the resources have been successful and are engaging for students because they are workshopped with students, and have realistic language and scenarios.

The Writing’s on the Wall is a script to be read in class. Janet says feedback from teachers and students has been good.

“It’s an early intervention tool in relation to graffiti tagging, but really it applies to any unhealthy risk taking behaviour,” Janet says.

The story involves a male student who has moved away from his familiar area to a new school. He becomes disengaged and ends up with the ‘wrong crowd’ and involved with risk taking behaviour. There are problems with the family, including drinking and violence.

“Comment we have had is that the students enjoy the whole class activity, boys are quite keen to read and the discussions afterwards allow students who may be having similar problems at home talk about that,” Janet says.

Janet says she believes this resource is successful because of the student input.

“It’s paramount the scenarios are all realistic and believable. What we are creating reflects what young people are doing.

“Our aim is to promote coping behaviours and help-seeking mechanisms, it is not about appointing blame.

“The subject of tagging is incidental. It’s more about the circumstances that surround this young man, and you feel real empathy for him as he goes down the path he does.

“Young people get an understanding of what led him to the risky behaviour, and they can talk about the choices he made and his parents’ choices. They can discuss what other choices he could have made and how he could have sought help.

“It gets young people to think outside the box and looks at what alternative strategies could have been used.”

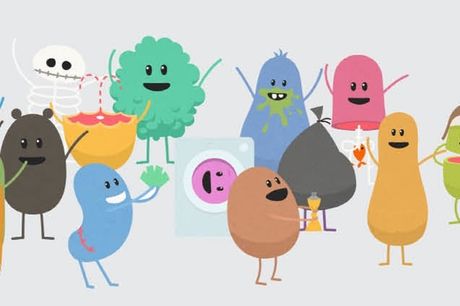

Dumb Ways to Die

Dumb Ways to Die is Metro Trains Melbourne’s ground-breaking campaign aimed at stopping risky behaviour around trains, following a growing number of accidents and deaths in previous years.

Dumb Ways to Die, which consists of a song, game and video as well as accompanying resources for the classroom, has ‘gone viral’.

The song has been viewed 65 million times on YouTube, the smartphone app has been downloaded 27 million times, the game went to number one in 18 countries and the app was number one in the USA, Canada, UK, Australia and New Zealand.

Ten thousand copies of the book were distributed to Victorian classrooms.

This popularity is unprecedented for a railway safety campaign. But has it worked?

McCann Australia devised the campaign for Metrorail. Group Account Director Adrian Mills says they planned for the campaign to be big.

“We wanted to take dry information and make it interesting for 12-20 year old males primarily,” Adrian says.

“This campaign is the opposite of most safety campaigns. Young males hate being told what to do with Newtonian force, but this is what most safety campaigns try to do.

“Safety campaigns tend to talk down to people rather than up to them: ‘Do this, don’t do that, or you will die’.

“We actually wanted this campaign to work, so our strategy was simple: If you have a message you want people to hear, make sure it’s a message that people want to hear.

“This campaign was beautifully executed, so the characters are fun but they have an edge to them as well.

“It’s black humour that is actually funny and therefore gives people credit. The fact that it’s a train safety campaign gives it that ironic edge.”

Three months after the campaign was launched Adrian says there was a drop in

the number of accidents recorded on Victorian trains.

Research was carried out which showed 53% of young people would behave

in a safer fashion around trains due to

the campaign.

Adrian says the conclusion is simple: Don’t force your message on to your audience; think about how you can communicate your message in a compelling way.