Volunteering at Addison Road Community Centre, Marrickville, NSW, during the pandemic.

On the radar at SBS

After retiring from professional football in 2003, Foster transitioned into a new career as a commentator with SBS, a broadcaster known for its commitment to multiculturalism.

He saw this role as a way to promote multiculturalism and advocate for social justice. “I was one of the few Anglo faces there, along with [former player and coach] Johnny Warren. We’d come out of the multicultural game, and we believed in multicultural Australia. It wasn’t just about a sporting contest – it was about inclusion,” he says.

SBS, which began broadcasting in Australia in 1980, is “an extraordinary organisation that Australia can be very proud of”, Foster says, as it plays a unique role in providing cultural education. “SBS brings the world to Australia, and it gave me a platform to talk to Australia.”

Foster’s work with SBS marked another turning point. “It’s where my advocacy went from unseen to seen,” he says.

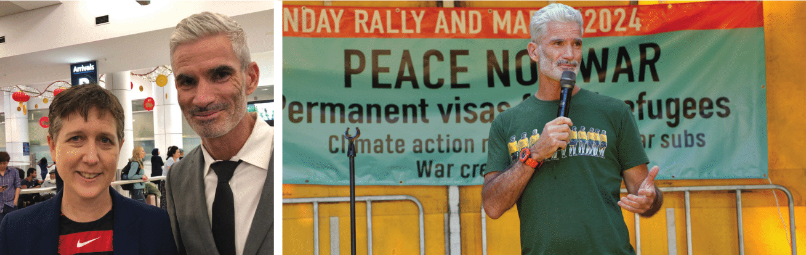

Today, Foster is a familiar face across Australia, using his platform to speak on issues such as First Nations justice, homelessness, refugee rights, and the rights of women and children in crisis.

Accepting our history

Foster believes that Australia accepting its history in all its complexity is the inflection point for building a strong, multicultural nation. “But there’s something in the Australian psyche whereby we can’t admit the injustice at the heart of the first contact – we haven’t internalised the reasoning of terra nullius in an effort to do better,” he says.

“Unless you’re a First Nations person, we’re all immigrants – I’m an immigrant from the boats from England in the early 1800s, and there’s nothing wrong with saying that.”

He underlines the importance of Australians talking openly and honestly about our history to break the cycle of hostility toward immigrants and refugees.

Education has a role in this too. In September, the NSW Education Standards Authority announced key changes to the history syllabus, so that students in Years 7 and 8 will study Indigenous peoples’ experiences of colonisation in Australia, including the Frontier Wars and the Myall Creek Massacre of 1838.

Foster believes Australia only stands to gain from plain speaking about our history. “When we’re courageous enough to confront it, to simply state it, ‘this is what happened, let’s just acknowledge our history’, then perhaps we can stop cyclically attacking different cultural groups who arrive,” Foster says.

Helping Hakeem

Foster came to national prominence as a human rights advocate during the campaign to free Bahraini refugee Hakeem al-Araibi from detention in Thailand in 2018-19.

A player on the Bahraini national team, al-Araibi fled the country in 2013 as he faced prosecution for attacking a police station during the Arab Spring of 2012, despite TV footage showing he was playing soccer at the time.

He was granted refugee status in Australia in 2017 but was arrested in Thailand while on his honeymoon due to an Interpol alert initiated by Bahrain.

Foster played a key role in mobilising support from the global football community and, thanks also to pressure from the union movement, human rights organisations and the Australian government, al-Araibi’s release was finally secured after 77 days in detention. He was granted Australian citizenship in 2019.

Hakeem al-Araibi’s story underscores the importance of humanising refugees. “The main challenge in the early months was making Hakeem human,” Foster says. “It’s always the same, recognising the equal humanity in others.”

Foster believes sport is uniquely placed to highlight international humanitarian issues. “The global game should naturally play a leading role – it makes perfect sense to me that someone who travelled the world playing for the Socceroos or Matildas, and who plays in a national team that is the most representative of multiculturalism, should be the ones to accept responsibility in this area,” he says.

Foster says Hakeem is doing well despite some challenges. “Life is complex after you’ve been tortured and been incarcerated and feared for your life,” he says. “But he’s safe and sound in Australia and he’s got great plans for the future, one of which includes his young son, who is four, playing for Australia.”

Australia welcomes Afghan women

Together with former Afghan Women’s National Team captain Khalida Popal, Foster was part of the international campaign to evacuate the team to Australia after the Taliban takeover in 2021.

They still play, for Melbourne Victory, but not in the international arena. The team is challenging governing body FIFA to allow them to compete in exile, and Foster fully supports this.

Also in 2021, Foster joined the campaign to bring a separate group of 15 young Afghan women to Australia from Kabul. All 15 were either school or university students at the time.

In the one-hour documentary Die or Die Trying, they trace their journey from hiding and making initial phone contact with community activists in Australia to their dangerous journey to freedom in pursuit of education and equality. Australia granted emergency visas and they were evacuated in October 2021.

“They’re like all refugees, they have to internalise massive amounts of trauma,” Foster says. “We’re still working on bringing their families here, but they have to get on with life at the same time while putting on a veneer of normality.”

Foster sometimes accompanies the women when they speak in schools, and their courageous stories often induce tears in students and staff alike.

“These are the stories Australians need to hear so we can build our muscle for compassion,” Foster says. “We have to hear stories of other people around the world in order to really be a genuine, great global citizen and partner for international law and human rights.”

Mixing sport and politics

Foster challenges the notion that sport and politics don’t mix, highlighting sport’s deeply political nature throughout history. He talks about Pierre de Coubertin, a founder of the modern Olympic Games, who used sport to promote imperialism.

“He felt that young French males were becoming too soft, and he wanted to use sport to keep them fit and healthy for military work,” Foster says. An aristocrat, de Coubertin based the pentathlon for the 1912 Olympics on the skills required of a cavalry soldier (fencing, pistol shooting, show-jumping, swimming and running).

“The history of sport is deeply political, and sport has a very proud history of political activism – apartheid in South Africa is a very good example,” he says.

An international campaign resulted in racially segregated South Africa being banned from the Olympics from 1964 to 1988 and the FIFA World Cup from 1964 to 1992, as well as other sports including rugby, cricket and tennis.

The boycott raised global awareness of apartheid and was instrumental in pressuring the South African government to end the practice in 1990.

“Life is political,” Foster says. “We have a lot to deal with in Australia and we can tell some of those stories through sport. Athletes are some of the most respected public figures and we can and should champion human rights.”

Matildas hold up a mirror

The rise of the Matildas tells us a great deal about Australia, Foster says. The nation’s most successful soccer team, the Matildas reached the quarter-finals of the 2015 FIFA Women’s World Cup in Canada and the semi-finals of the 2023 World Cup in Australia and NZ.

The Matildas made fans of millions of us. They may have lost their semi-final to England 3-1, but the match became Australia’s most-watched television event, with 11.15 million viewers at its peak.

Foster says the Matildas’ struggles and successes reflect a larger issue of gender equality in Australia. “I want all the men who were so against women’s sport to see the Matildas holding the World Cup trophy,” Foster says. “I really want for the team to lead that conversation.”

Off the field, the Matildas have also been champions of gender equality. The players are members of their union, Professional Footballers Australia (PFA), and in 2015, they went on strike for better pay and conditions.

At the time, Vice-Captain Joey Peters also worked as a cleaner to support herself while training. The strike led to annual salaries of $41,000 (up from $21,000) as well as better conditions.

But it didn’t end there. In 2019, the Matildas again broke new ground by negotiating equal pay with the Socceroos through a joint collective bargaining agreement with the Socceroos and Football Australia, one of the first of its kind in the world.

“This new deal is enormous,” player Elise Kellond-Knight said to the ABC at the time. “As a female footballer, it’s kind of what we’ve always dreamed of. We’ve always wanted to be treated equal.”

Socceroos step up

Foster believes unions play a crucial role in bringing about social change. “The human collective is the most important vehicle we have for progress, change and protection of people everywhere,” he says.

The Socceroos have a proud history of taking a stand, going on strike in 1997 at the FIFA Confederations Cup in Saudi Arabia over pay and conditions and highlighting human rights issues in the host nation. “It sparked the professionalisation of the game in all aspects,” Foster says. “And it educated a new generation of players on human rights.”

The team also made strong statements ahead of the 2022 World Cup in Qatar, advocating for the rights of migrant workers and the LGBTQI community.

Foster says unions are essential in balancing the power of capital, enabling workers to shape their society. “Unions don’t just bargain for pay and conditions, they also bring masses of people together to act in unison on a vast range of social and political issues.”

World game, global citizens

One word comes up over and over in conversation with Foster: global. “The world is coming closer together, not getting further away, and Australia has to see ourselves as global citizens,” he says.

As climate change accelerates, creating more refugees and necessitating greater global mobility, he warns against insular movements such as Trumpism and Brexit, which emphasise exclusion and difference rather than similarities and inclusivity. “There’s only so much fence and so much barbed wire we can possibly put up,” he says.

In this increasingly interconnected world, he says, Australia can help create a compassionate global community through strengthening our sense of shared humanity.

“We have to hear stories of other people around the world,” he says. “Refugees are people, they’re human, they have families, they have children. They’re just like us but under different circumstances.”