Damian Nelson is a Queensland teacher and Network Coordinator of the Solidarity Journeys program. Solidarity Journeys is a collective of educators, returned volunteers and aid workers – informed by the principles of human rights and ecological responsibility – with a commitment to forming and strengthening attitudes of solidarity between people of the ‘Minority World’ and people of the ‘Majority World’.

From his 15 years of experience developing immersion programs for students, Damian has a depth of knowledge regarding the professional considerations that come with conducting such a journey.

The journey

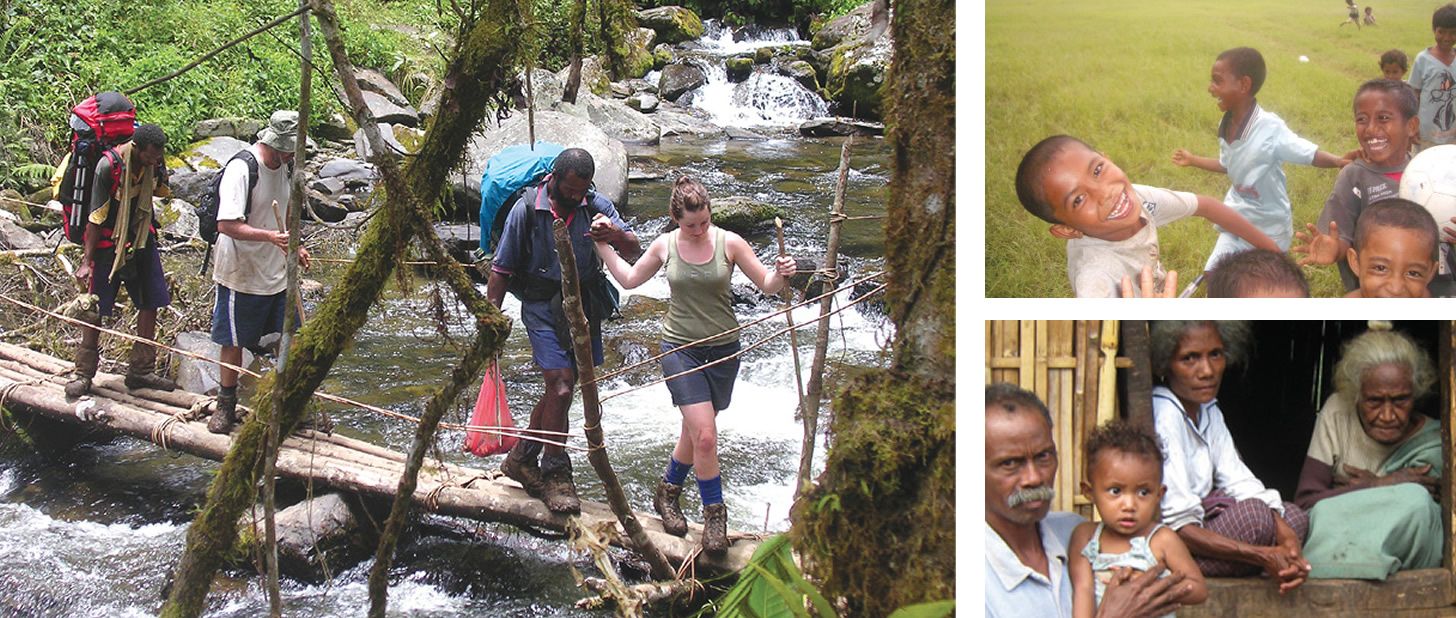

A Solidarity Journeys program runs over 12-13 days, with students living in various locations and experiencing the nuances of the culture of the country they visit.

“The first couple of days are spent in a major centre, in living conditions that are basic but quite comfortable to allow students time to adjust to the new environment.

“In this time students would visit sites of historical, cultural or political significance.

“For faith based schools, students may connect with church or other aid agencies to gain insights into their work.

“The next stage involves journeying to smaller centres until eventually being in the care of a small remote village community for the core element of the journey – the ‘immersion’ experience.

“Typically we would be cared for by the church or parish community – accommodation could be in groups under the supervision of the teachers in local village accommodation, or in a community building or in a church facility such as a convent.

“This element of the journey is often the experience that has the greatest impact on the students.

“After a few days in the village we return first to a small regional centre, then back to the major centre,” Mr Nelson said.

Purpose is important

Stressing the importance of being clear about the purpose of a journey – Mr Nelson drew comparison between a solidarity and service model, highlighting the ways in which a trip founded on a service model can create a superiority divide rather than promote empathy among students.

“I have witnessed some schools visit communities in PNG and East Timor who spend a few days painting classrooms.

“When they leave the members of the local community have said to me ‘do they think we are incapable of using a paintbrush’?”

In considering the purpose of a trip, Mr Nelson said one must be mindful of what they’re really setting out to do – to provide a service that locals are likely capable of providing themselves, or to foster understanding and empathy between cultures.

“We do not operate out of a service model but a solidarity model. The service model reinforces the stereotype that ‘we’ are superior to ‘them’ whereas a solidarity approach acknowledges that ‘we’ – us and them together – are equal with different strengths.

“The purpose of our journeys is to engage with the people and communities we visit as equals to gain insights into the realities of their circumstances, form relationships, learn from each other and critique our own culture from their perspective.

“Once a relationship is formed between the respective communities, then a conversation can begin about how each can be of service to the other.”

Risk management and cultural context

Mr Nelson said risk awareness and risk management are the most important considerations for the teachers who are planning and implementing journeys such as these – this includes awareness of the cultural context of the host country.

“It is very important, indeed crucial that the person leading the group be intimately familiar with the culture and context of the host communities.

“What is needed is a degree of familiarity that has been gained through being ‘in-community’ for quite an extended period of time.

“Teachers who have worked in the host community for a year or more and have developed close relationships are likely to be intuitively aware of the risks – and know what they don’t know.

Briefing sessions for students before, during and after the trip are also integral.

“These sessions would include instructions to seek and act on the advice of medical practitioners with expertise in travel medicine regarding vaccinations and precautions to take while on the journey to minimise the risk of disease.

“The briefing sessions also need to provide information about the destination in terms of its history, geography, climate, political circumstances, culture, religions and traditions.

“Students need to be sufficiently prepared so as to minimise the degree of culture shock, to be able to suspend judgement when they come across cultural practices they may find somewhat confronting, and to avoid behaviours that are culturally insensitive or may offend their hosts.

“Equally importantly, opportunities need to be provided throughout the journey for students to debrief their experiences to allow for adequate processing of the experiences.

“Comprehensive debriefing sessions two or three weeks after returning home are also crucial not only to reinforce the learnings gained on the journey, but to manage the culture shock students may experience when returning home.

“A common experience, particularly after being in a village community living very simply, is to be overwhelmed by the absolute overabundance of goods in our massive shopping centres.”

Whether or not a program is able to be implemented at a school depends on whether school leadership sees the program as being valuable, and whether there is the capacity to adequately resource in terms of time and staff.

“It must be acknowledged that schools have many pressing priorities.

“For many schools there are very good reasons why offering a Solidarity Journey would not be one of those priorities.

“It is disappointing that in some schools teachers with a passion for offering these opportunities to their students have been frustrated because of lack of resources.

“Concern for the safety of students is of course a reason why some schools choose not to offer their students these programs but we need to be careful of an attitude of risk aversion such that we stifle opportunities for students to have such wonderful life changing experiences.”

Rewarding journeys

Mr Nelson said the way students responded to the experiences along the journey and afterward was inspiring.

“I am reassured that the future is in safe hands; that there will be many good people doing good in the world.

“I can see that my classes are full of good kids who are going to grow into good adults.

“To be a part of that formation process is indeed a great privilege,” Mr Nelson said.

To find out more about Solidarity Journeys visit www.solidarityjourneys.net.au or email dnelson@solidarityjourneys.net.au.