Australian academic Amanda Tattersall

Striking in Australia

Despite NSW teachers and nurses taking industrial action in recent years, it’s difficult to know exactly why Australia has not experienced quite the same widespread union activism.

In a 2023 article for The New Daily, journalist and economist Alan Kohler declared “it’s virtually impossible” to strike in Australia “and has been for more than a decade”.

Since the Howard years, conservative governments at a state and federal level have passed laws that have inhibited union action. However, the current federal Labor Government has passed three tranches of industrial relations reforms over the past 18 months aiming to redress the balance (read more on p25).

But it’s important to remember, Tattersall says, that strikes do still happen in Australia.

The IEU’s highly successful “Hear Our Voice” campaign of 2022-23 saw teachers and support staff at Catholic systemic schools in NSW and the ACT take two full days of strike action, including a joint rally with the NSW Teachers Federation, winning historic pay rises in the process.

The IEU had to jump through many hoops to strike, including applying to the Fair Work Commission for protected action ballot orders and engaging a third-party balloting agent to conduct voting.

While the industrial landscape varies in the US and Australia, in both countries, workers do take illegal strike action on occasion, sometimes as a form of civil disobedience, IEUA NSW/ACT Branch Industrial Officer Michael Aird says. The NSW Teachers Federation was fined $60,000 for striking during their 2022 “More Than Thanks” campaign.

Despite the restrictions on strikes in Australia, Tattersall argues that striking is only one weapon in the Australian labour movement’s arsenal. Unions can still achieve transformative change, she says, with limitations presenting an invitation to think creatively, experiment, and reimagine how they can exercise power.

What can be learned

“Borrowing successful techniques and strategies from campaigns in one country and translating them to another is nothing new,” says Tattersall, who has devoted a lot of time to adapting labour movement work across borders.

To her, one of the biggest lessons of the US union boom is the power of localised union activity. She argues that the decentralised nature of the fight has propelled the union revival in the US.

For Kallas, the union boom demonstrates the power of strong leaders who can see “when the conditions are ripe” for action and can capitalise on that opportunity.

Perhaps the biggest takeaway from the union boom is what Kallas calls “the contagion effect”. He points to a series of earlier teacher strikes in the US. The Red for Ed movement kicked off in West Virginia in 2018 when teachers and support staff walked out.

They soon inspired staff in other schools in state after state. “It was like a wildfire,” Tattersall says.

Kallas has seen this contagion effect across industries all over the country through the union boom and he believes it can continue across borders. He hopes the Labour Action Tracker might play a small role in that.

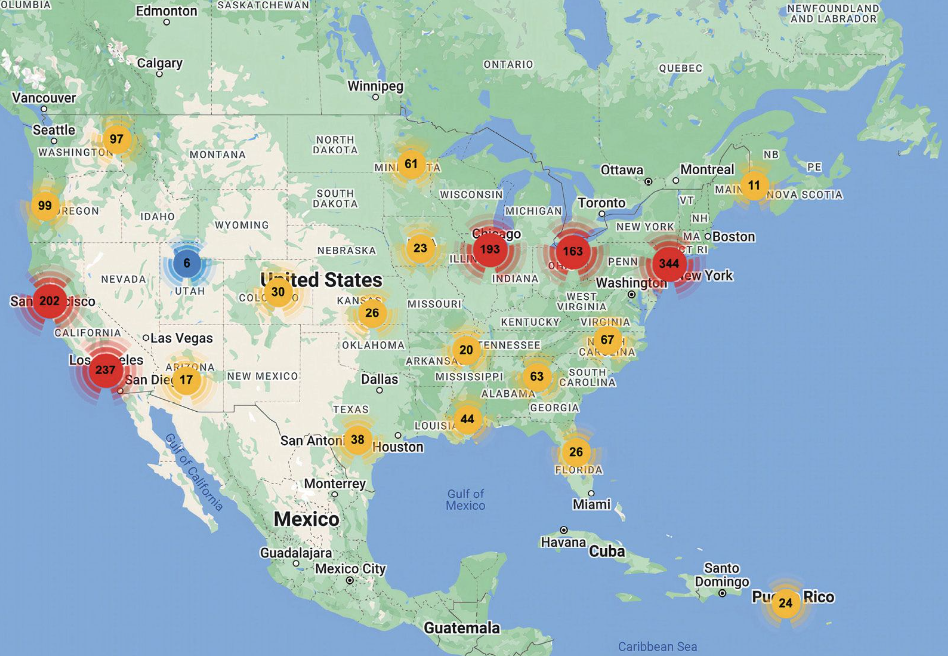

A global strike map

Scholars and activists from several countries are trying to “create at least the beginnings of sort of a global strike map report”, Kallas says.

Inspired by the work of Kallas and his team, researchers in countries including Brazil, Türkiye, and the UK are working on their own labour action trackers, with an effort underway to start a global database. “That would be exciting,” Kallas says.

The ultimate goal is to create a tool that would not only provide accessible data for policymakers and academics, but also help unite workers internationally.

Back in Australia, there is great potential for such a tool. Aird believes there’s power in hearing about what’s happening in other countries because we live in a globalised economy. “When workers are brave enough to stand up, it encourages other workers to do the same thing,” he says.

Looking ahead

With the US now in a pivotal election year, the impact on the union boom remains to be seen, but Kallas expects the revival to continue through 2024.

Tattersall is confident about the outlook for Australian unions. “We’re in a position to turn a fairly good context and a lot of interesting insights into action,” she says. “The hope is that this can be mixed together into something really exciting.”