What do teachers believe enhances their efficacy? Dr Graham Hendry from the Centre for Educational Measurement and Assessment at the University of Sydney, and Mary Ryan, Head of Professional Learning and Accreditation at Catholic Schools NSW, explore this question.

Why is teacher efficacy important?

Teachers with higher efficacy are more motivated, have a greater sense of wellbeing and persevere in helping children to learn (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2007; Tschannen-Moran & Barr, 2004; Zee & Koomen, 2016). There are two types of teacher efficacy: self-efficacy is a teacher’s confidence or belief in their own capability in a particular area of practice (for example, in teaching reading); collective efficacy is a teacher’s confidence or belief about their colleagues’ and/or whole school’s potential to be successful in a particular area of practice.

We already know that there is a positive relationship between both teachers’ self and collective efficacy and students’ achievement (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2007; Tschannen-Moran & Barr, 2004). However, as vital as it is in education to understand how to support and develop teachers’ efficacy, we know little about what teachers themselves think enhances their efficacy.

What we did

We conducted a small-scale interview study with 12 primary school teachers in western NSW about naturalistic influences that they thought had led to them developing their efficacy or made them feel more confident to teach reading. We focused on reading because the ability to read enables people to engage in education, acquire knowledge, and participate fully in society.

We held individual private interviews with teachers at their schools. Standard questions included: “Can you please tell me about a time when you have been successful in teaching reading?”, “How did this experience influence your confidence (if at all) in your ability to teach reading?”, and “What other experiences or influences do you think have made you feel confident in your ability to teach reading?”.

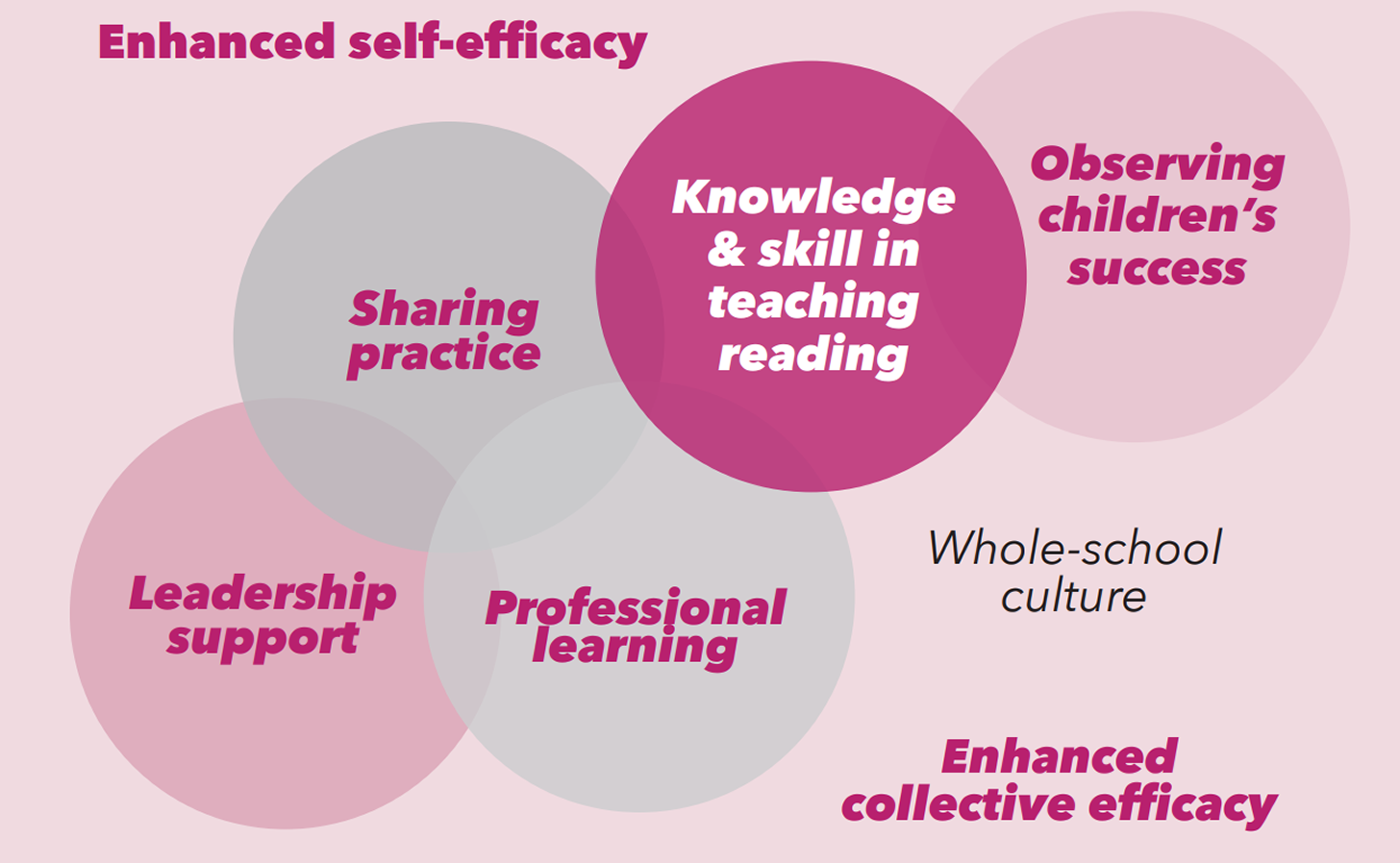

Both of us then read and re-read the interview transcripts to analyse them for ‘themes’, or things that were common to all teachers’ views about what enhanced their efficacy in teaching reading. Five themes emerged from what teachers said.