International border closures have significantly impacted the international education sector in Australia. Organiser Orlando Forbes looks at what is happening in a sector where the IEU represents many members.

Private education providers for overseas students in Australia have gone through several tumultuous journeys over the years, most recently due to the COVID-related closure of international borders.

For more than 25 years, the Independent Education Union has represented employees in private business colleges, English language intensive courses for overseas students (ELICOS), and private vocational education providers throughout Australia.

In March 2021, English Australia, the peak body for the ELICOS sector, reported its “worst ELICOS commencement number in 14 years”, demonstrating a 43.3 percent drop in students beginning new courses. Recent media reports describe the outlook for ELICOS as “dire”, saying the sector has been “crippled” by COVID-19.

That ELICOS has suffered a huge blow is beyond question. An industry that relies completely on international students to operate is indeed in trouble when those international students are unable to enter the country. It is in even greater trouble when the wage subsidy keeping colleges afloat is ended, as JobKeeper was at the end of March 2021.

State of play

At the time of writing, large employers such as Kaplan International, Ability English and EC English have either closed their doors or put the ELICOS arm of their operation into hibernation, as have a substantial number of smaller players. And although there has been some limited assistance from the Federal Government in the form of a $53.6 million rescue package for the sector, there is an expectation that other employers will also close their doors in the weeks and months to come.

The Federal Government has signaled its intention to rethink the international education sector, having already begun moving towards a new approach with the release of a paper entitled Connected, Creative, Caring: Australian Strategy for International Education.

The paper notes: “Our institutions are facing a drop in onshore student numbers that will continue for some years to come and a new strategy is needed to adapt to the changes brought on by the pandemic.”

In much the same way, we need to consider what lessons we can take from the pandemic and what we want the sector to look like when the world stabilises. As stakeholders in the sector, how does the union want to ‘build back better’?

COVID-exacerbated casualisation

Although they are known in the sector as ‘permanent casuals’ or ‘long-term casuals’, the average casual ELICOS teacher can be categorised as what David Peetz (2020) has called an ‘unsubstantiated casual’.

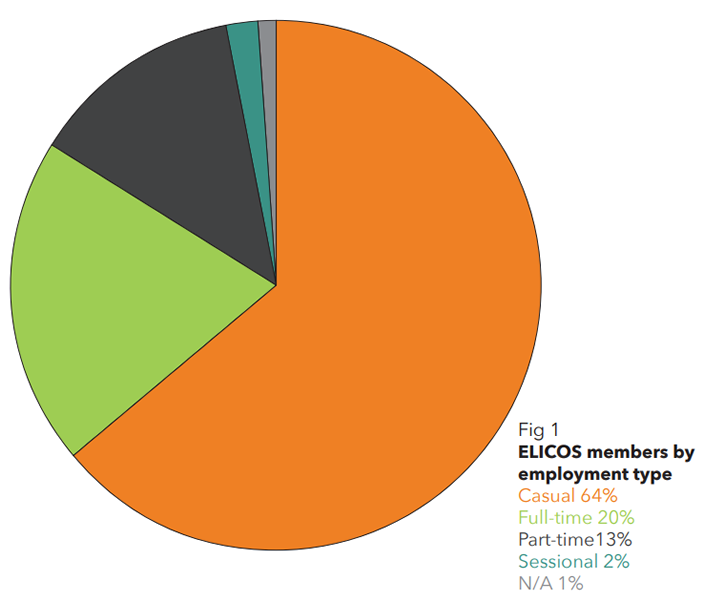

That is, a worker who has been with their employer for more than one year, with reasonable expectations that they will continue to be with their employer in 12 months’ time, and who has regular pay and hours. At a great many ELICOS colleges, this describes most teachers. Some 64 percent of ELICOS IEU members were listed as casual before the pandemic.

It is common for a teacher to teach the same hours Monday to Friday, sometimes for as long as 15 or 20 years. ELICOS teachers in this situation occupy an unusual space: they are employed in a ‘worst of both worlds’ arrangement, somewhere between casual and permanent, with no job security or protection, yet a level of commitment not typical of casual employment is expected of them.

“In practice, the flexibility isn’t really there,” said one long-term casual ELICOS teacher. “At my college we have a teaching schedule based on four-week blocks. As a general rule, if we request [unpaid] leave for some of that time our employer forces us to take the entire block off, meaning that we are penalised one month’s wages.”

Data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics from December 2020 tells us casuals were hardest hit by job losses during the pandemic. The ELICOS sector was no different, as colleges shed large numbers of these employees.

This was particularly distressing for those casuals among our membership who had been employed on a long-term, regular basis. These teachers found themselves suddenly cut loose to look for a new career in the middle of an economic downturn without warning or support, after having given many years to their job.

Some ongoing members were among the last to lose work during the pandemic – and those who did were entitled to redundancy pay, notice or payment in lieu of notice, and the paying out of accrued annual leave. This put them in a much better position to transition to something new.

Wage theft and COVID pay cuts

Early in the pandemic, colleges tried to push losses onto teachers. One college, International House, attempted to impose a 15 percent below-award wage cut on staff across the country, until union members forced this multinational employer to rescind.

IEU branches have recovered large amounts of underpayments in the sector. For example, in Melbourne, IEU Victoria-Tasmania recovered just under $200,000 of unpaid member entitlements from the Australian National College of English, due in part to its below-award slashing of pay to $35 per hour after moving from face-to-face to online teaching.

The IEU also recovered tens of thousands of dollars in unpaid superannuation and entitlements from another Melbourne-based college, Languages Across Borders.

These two issues are broadly related, in that research shows that not only are casuals more precarious than their ongoing counterparts, but that this precarity places them at a higher risk of wage theft.

From the ground up

As the sector reboots, we need to focus on building a better industry. Rather than wage theft, precarious employment and substandard working conditions, we hope the sector builds in assurances of education quality, where teachers are treated in a way that is reflective of the quality work they are tasked with performing. We will not get there if things continue the way they were.

A 2019 risk assessment report from the Tertiary Skills and Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA) reveals that education providers that were high-risk to students demonstrated persistently higher levels of casual academic staffing. “High proportions of casual academic staff [are] considered to pose risks to the continuity of support for students and adequate support systems for casual staff,” the report said.