Now let’s think about our education system. Can we, hand on heart, say that 98 per cent of our students are encouraged to engage with the arts during their education? Are we able to honour Sir Ken’s legacy with the knowledge that creativity is at the core of our education system? And if not, why not?

Better cognition in all areas

First, let’s consider what is gained from an arts-rich education. The list of skills enhanced by arts education is extensive, validated by research commencing in the 1950s and reworked from every angle around the world ever since. Again and again, it has been shown that active engagement in the arts improves academic and often social outcomes for students in both primary and secondary education.

The underlying question in more recent research is reasonable: Were these students always going to get ahead thanks to privileged backgrounds? Which brings us to causation versus correlation. Two large American studies undertook to answer this.

One was the Dana Arts and Cognition Consortium, which brought together cognitive neuroscientists from seven US universities. Were smart, rich people better able to access the arts, so their results across all areas were likely to be better?

They found that, regardless of socio-economic background, an interest in the performing arts leads to higher states of motivation that produce the sustained attention necessary to improve performance. And the training of attention leads to improvement in other areas of cognition.

Zeroing in on my particular interest, the study demonstrated specific links between high levels of music training and the ability to manipulate information in both working and long-term memory; substantial improvement in numeracy and geometric skills; and more highly developed skills in reading and sequence learning.

An even bigger US study, Champions of Change (2000), followed 20,000 young people for 10 years to see if engagement in the arts made any difference. Again, regardless of background, young people who engaged in the arts: had better academic results; were less involved in substance abuse; had higher levels of civic engagement; and music students exhibited advanced maths proficiency and higher overall academic superiority over non-music students.

From my own experience over decades mentoring in the arts, it has always struck me that the arts offer an alternative entry point into academic study for students who are otherwise disengaged. Time and again I heard teachers talk about “that student” who was troubled or otherwise unresponsive who suddenly blossomed when they found a “way in” through the arts.

So much upside

If these reasons are not sufficient, there is also considerable community support for the arts in our lives. The Australia Council research notes that the largest increases since the last such survey (in 2016) have been in the proportion of Australians agreeing on the impact of arts and creativity on child development (63 per cent); on our sense of wellbeing and happiness (56 per cent); on helping us deal with stress, anxiety or depression (56 per cent); and on stimulating our minds (64 per cent). What’s not to like?

The report went on to note that at least six in 10 Australians agree arts and creativity impact our ability to express ourselves (64 per cent); our ability to think creatively and develop new ideas (62 per cent); on our understanding of other people and cultures (60 per cent).

One in two Australians agrees that arts and creativity are important in shaping and expressing Australian identity and in building creative skills that will be necessary for the workforce. Surely these are critical factors enabling us to recover and regenerate in post-pandemic Australia?

A resounding majority of the 9000 respondents in the Australia Council study believe the arts should be an important part of education (73 per cent), with similar percentages agreeing that the arts in Australia reflect the diversity of cultures present in Australia (71 per cent) and the arts help you to understand perspectives that are different to your own (71 per cent). Surely these are the building blocks of education.

Indeed, the arts help a child achieve all manner of good outcomes beyond the arts. But the arts are important because they are good in themselves, because they are inspiring, because they make us feel and think differently about ourselves and about the world around us. That is their greatest and unique value.

Persistent impediments

With decades of convincing literature, one would think that mandating an arts-rich education is a no-brainer. Yet, there are persistent impediments to embedding the arts in education in Australia, whether at primary or secondary levels.

Overcrowded curriculum

My area of greater familiarity is primary school, but this problem does not seem to decrease as one shifts gaze to secondary school. Schools are expected to play ever-increasing roles in loco parentis, whether it be in issues of safety, health, wellbeing or social skills. The intensifying focus on standardised testing, and the impact these test results have on a school’s marketability and therefore funding, is another factor that has robbed students of time they might have spent developing creative arts skills and knowledge. The reasons for these tectonic shifts are far too wide-ranging for this article, but with each additional layer of external pressure, the squeeze on the arts becomes greater. Changing this will take a ground-swell of dissatisfaction with the current balance.

Support for teachers

With music in primary schools a focus of my professional work over the last 20 years, I was aghast to learn how unsupportive pre-service training for generalists is. Small wonder it has led to an overall lack of confidence in teachers to throw themselves into arts teaching, either intensively or as a platform for other subjects. In a seminal study for Music Australia in 2009, Dr Rachel Hocking revealed that only about 1.5 per cent of pre-service training for primary generalist teachers in Australian universities was allocated to compulsory music training. That is rather like going in to teach German having only studied it for two days. Ludicrous? Of course. But that is what we are expecting from our generalist teachers in primary schools. No wonder it doesn’t rise to the top of the “must do” pile, among all the other pressures on teachers.

One encouraging sign to emerge from this COVID-19 time is the acceleration of online learning, which may help address some of this problem through well-targeted, in-service training, offering less confident teachers a new national network of mentors or “buddies”.

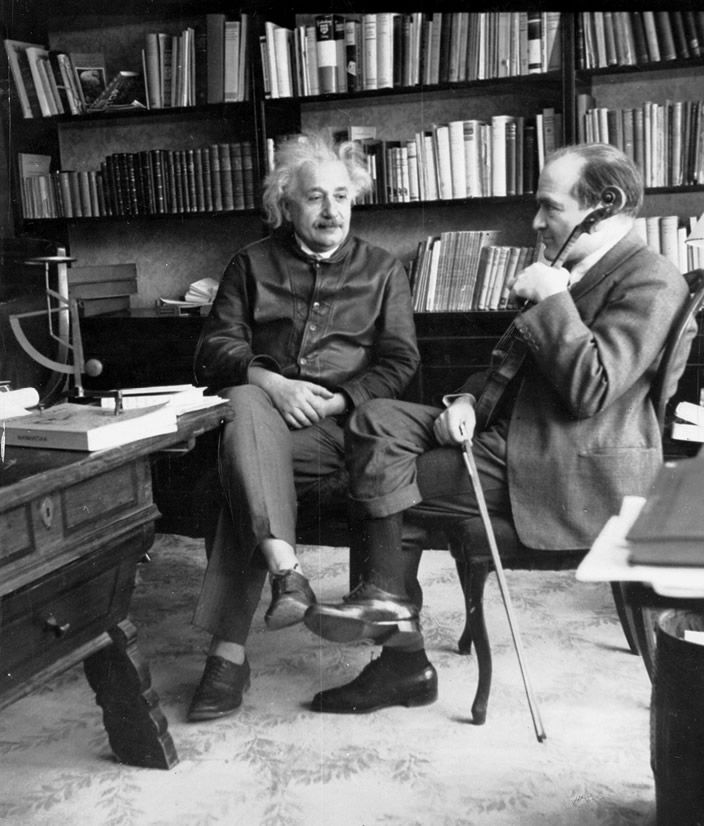

Parental pressure over “employability”

Even pre-COVID, educators have had to respond to community pressure for augmenting “marketable” skills in students. The emphasis on STEM subjects is understandable, but ignores the fact that even Einstein found playing his violin a necessary adjunct to his research. Dr Ian Frazer, the remarkable Scottish-Australian scientist who, with the late Dr Jian Zhou, developed the cervical cancer vaccine, insists that listening to classical music gives him the “headspace [he] needs to do his work”. This binary approach of STEM rather than STEAM is everyone’s loss. Our politicians have underscored this approach most recently with the proposal to double the cost of humanities degrees, implying they produce “less employable” graduates – despite the fact that more than 60 per cent of federal politicians have a humanities degree.