In Finding the Heart of the Nation: The Journey of the Uluru Statement towards Voice, Treaty and Truth, Thomas Mayor has created an unforgettable work of spirit, struggle and survival. He talks to IEU journalist Monica Crouch about the power of collective action, and why he loves teachers.

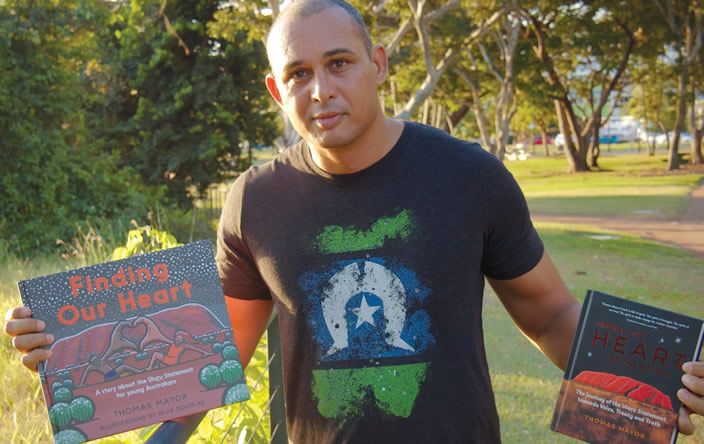

Torres Strait Islander man, author and unionist Thomas Mayor says his book, Finding the Heart of the Nation (Hardie Grant, 2019) is his gift to the campaign for constitutional recognition for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

It certainly is that, but it’s also more than that: it’s a gift to the entire nation. Mayor’s book gives voice to more than 20 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who help pierce the “Great Australian Silence” that denies Indigenous people their rightful place in their own country.

In this beautifully written, generous and compassionate work, with its breathtaking photography and intricate drawings by Mayor's daughter, Shayla, we join Mayor as he tucks the Uluru Statement from the Heart canvas under his arm and takes it to the Australian people. Featuring artwork by a group of Anangu women artists led by Rene Kulitja, the original canvas is signed by more than 250 delegates who attended the historic First Nations Constitutional Convention in 2017 at which the statement was endorsed.

Along with Mayor, we are welcomed to country and invited to hear stories of history, hardship, community and overcoming. Voice by voice, story by story, we learn more of Australia’s past and gain an understanding of the Uluru Statement’s inclusive vision for our collective future.

Righting wrongs

But first, we need to talk about Black Lives Matter. “The protests in the United States over police brutality and racial prejudice have provided the opportunity for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people here to hold the mirror up to Australia,” Mayor said.

“Through the Uluru Statement, we have already tried telling the Australian people that we suffer from systemic racism here. In the statement, we point out that ‘Proportionally we are the most incarcerated people on the planet. We are not an innately criminal people.’

“If we were to update the statement today, we would likely add a line about more than 430 deaths in custody since the 1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, and how in 2015, a Dunghutti Aboriginal man, David Dungay, was killed in much the same way George Floyd was – on film, crying that he couldn’t breathe. For David’s family, there has been no justice.”

Over the long weekend in June, tens of thousands of people throughout Australia united in protest over Aboriginal deaths in custody, reflecting what Mayor describes as justifiable anger over the nation's proud notion of a ‘fair go’ not being afforded to Indigenous people.

“I hope it will be our generation that rights the wrongs of the past and addresses the Indigenous plight in the present,” Mayor said. “The way to do that is to walk with us both on the streets in protest and by sharing the hope in the Uluru Statement from the Heart.”

Ripe for change

Throughout his travels, Mayor found the Australian people greeted his book with the same positivity as they have the Uluru Statement. “Like the Statement, it is just a matter of people reading it – listening, really – and wanting to understand how we can repair the damage done by colonisation and more than 100 years of hurtful policy,” he said. “I think the Australian people are ready for the truth-telling and are looking for hope.”

The Uluru Statement takes that hope and translates it into two positive actions: enshrining a First Nations Voice to Parliament in the Australian Constitution; and establishing a Makarrata Commission (meaning “coming together after a struggle”) to advise on agreement making and truth telling between governments and First Nations people.

Constitutional change is crucial to avoid one government’s progress being wiped out by the next. History is littered with examples: police and political intimidation put an end to the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association (1924-27); the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) was established by the Hawke government in 1990 and abolished by Howard’s in 2005; and in 2013 the Abbott government defunded the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples, so it was forced to wind up in 2019.

But attitudes are shifting: Mayor has found consensus where once there was conflict. “Across the spectrum of political ideologies, I found it common that with the facts and logic behind a constitutionally enshrined Voice to Parliament, support was forthcoming,” he said. “It is this support from across the political spectrum that tells me the nation is ready. We just need the political leadership and campaign resources now to win a referendum.”

Class act

“I love teachers,” Mayor declares. “From the moment the Uluru Statement from the Heart was endorsed and made public, teachers around the country didn’t hesitate to start teaching children about the gift that it is – they didn’t wait for curriculum or teachers’ resources, they just did it,” he said.

In Finding the Heart of the Nation, Mayor describes a visit to Thursday Island, his ancestral home, where he visits Our Lady of the Sacred Heart School and talks to an assembly of excited students about the Uluru Statement.

“This is one of the reasons I wrote the children’s book, Finding Our Heart,” Mayor said. “Teachers teach kids, kids go home and teach their families. I think it is vital that teachers are supported to do this work by the system. I understand that teachers are under-resourced and are often going to great lengths, at personal cost, to provide the education the nation’s children need and deserve. This important work should not be a teacher’s burden, it should be Australia’s priority, collectively.”

Collective action

A wharfie by trade, Mayor is the Deputy Branch Secretary of the Northern Territory branch of the Maritime Union of Australia (a division of the CFMEU). From the 1936 Torres Strait Islander maritime strike against the exploitative pearling industry to the Wave Hill Walk-Off of stockmen and servants protesting stolen land and wages in 1966, Mayor sees workers acting collectively through unions as central to social justice.

“Like all campaigns for progressive social change in our history, the union movement is integral,” he said. “We cover millions of workers who have their own networks and families that can ultimately move a government to put the First Nations Voice question to the people, before voting ‘Yes’. We have already seen great support from unions, and soon, through the ACTU, we will be delivering Uluru Statement Advocacy courses to help educate and empower union members to participate in the campaign.”

Mayor says union-minded people readily understand the notion of a constitutionally enshrined voice. “It is simply a call for a First Nations’ representative body (a union) guaranteed by the rule book of the nation (the Constitution),” he said.

Destruction of heritage

But wait, there’s one more issue we still need to talk about. On May 24 this year, mining giant Rio Tinto blasted the Juukan Gorge rock shelters in remote Western Australia that held evidence of Aboriginal occupation dating back 46,000 years. “I was saddened and disgusted that Rio Tinto could destroy such sacred cultural treasures without legal repercussion,” Mayor said.

Reducing this heritage site to rubble reflects a broader, nationwide problem. “It indicates that our laws remain frozen in time – a time when First Nations people were excluded from the Constitution on the basis of us being a dying race,” Mayor said. “This indictment on our nation reinvigorates my resolve to pursue the Uluru Statement’s call to establish a constitutionally enshrined First Nations Voice, because without a strong voice in the centre of decision making, we will continue to struggle to see that laws and policies are updated in a way that protects Indigenous peoples and our culture.”