Research suggests that the prevalence of children being diagnosed on the autism spectrum is increasing, with a recent study estimating that 1 in 68 school aged children are being identified as on the spectrum. Journalist Jessica Willis writes about recent work in this field.

In Australia, the majority of children on the autism spectrum attend mainstream schools so it is likely a teacher has at least one student on the spectrum in their class.

Students on the autism spectrum have diverse needs when it comes to learning support, which can sometimes be challenging for a teacher to address.

However, there is a wealth of knowledge in our school and broader communities that can equip teachers and teacher aides to help their students succeed.

Helen McLennan is a Professional Learning Facilitator at Autism Queensland and part of a team that provides evidence based training for anyone who supports and works with people on the autism spectrum.

She has a long background in teaching and occupational therapy and her area of expertise is in classroom practice.

McLennan discussed the importance of embracing the strengths and supporting the challenges of students on the autism spectrum.

McLennan said that being on the autism spectrum means that a person has a different way of perceiving and experiencing the world around them.

“However, it is important to understand that the spectrum is very fluid and each student will be unique in how they perceive and react to the world,” said McLennan.

How being on the autism spectrum affects students

McLennan said students who are on the autism spectrum have some difficulties that impact their day-to-day life in two broad categories: social communication and interaction; and restricted, rigid and repetitive behaviours.

Within the first category, students might have difficulty with:

- understanding what you say

- eye contact and other nonverbal body language

- making conversation

- navigating social interaction and maintaining friendships, and

- taking things literally.

In the second category, students might exhibit:

- resistance to change and the need for predictability

- hypersensitivity to sensory information in the classroom (such as intense reactions to certain sounds, movements, lights and patterns)

- outstanding skills in certain areas

- preoccupation with certain topics, and

- repetitive behaviours (such as flapping, body rocking).

Students on the spectrum, especially adolescents, have a higher prevalence of conditions like anxiety and depression.

“Students may also present differently in different environments which means that how support is structured in a classroom matters,” McLennan said.

Classroom support structures

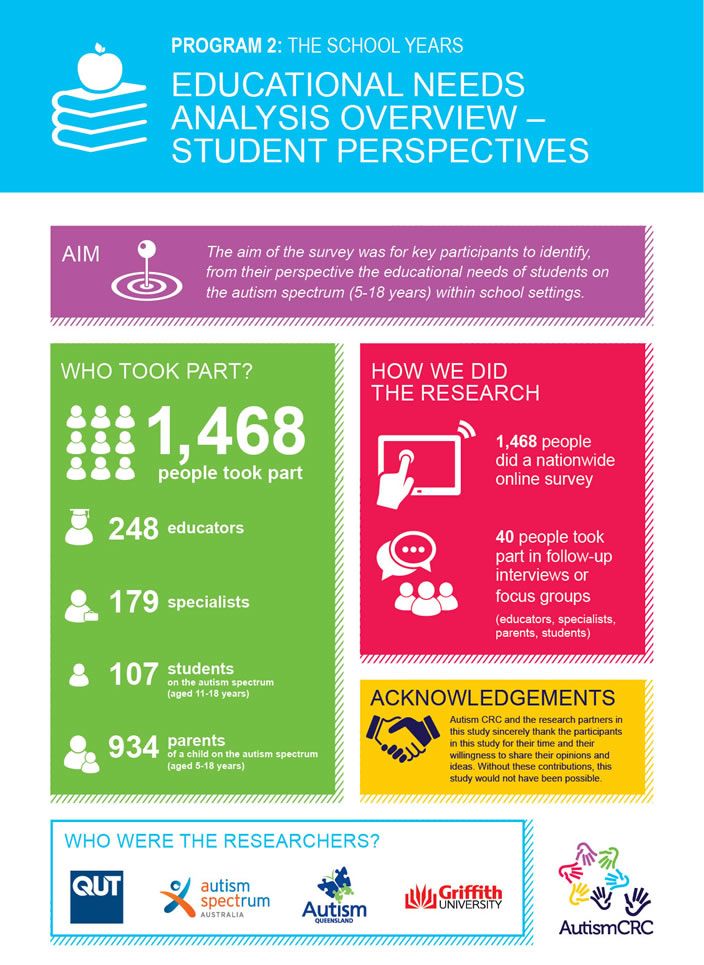

According to the 2015 Australian Autism Educational Needs Analysis, students on the autism spectrum rated the following school activities as the 10 most difficult:

- planning for assignments

- working as part of a group

- handwriting and being neat

- coping with change

- coping with bullying or teasing

- speed at which they completed handwriting

- copying information from the board

- doing homework

- staying calm when other kids annoyed them, and

- staying calm when the classroom is very noisy.

McLennan refers to the findings of this study when developing classroom support structures.

“Firstly, incorporate technology such as laptops or tablets to help students complete basic school work, for example as an alternative to handwriting.

“Second, support executive functioning skills and the need for predictability by helping with planning and organisation as much as possible.

“Visual schedules that are referred to throughout the day provide a plan to follow, support transitions and show any changes to regular timetables, such as a relief teacher.

“It can be as simple as a teacher writing on the board the three things that will be taught today or what equipment is needed for a lesson.

“One-on-one support is also a great strategy so that a student has extra time to go through and understand tasks.

“This also extends to additional support for any big changes, like moving to secondary school, which need to be planned for well in advance.

“Another strategy is ensuring students can take a break to calm down if they need to.

“Many schools make sensory rooms or spaces, like a small cubby in the classroom, available to help with sensory needs and emotional regulation.

“Identifying a key person that a student can go to at any time is also a good strategy – someone who they feel comfortable with.

“Teachers should be aware of students who may be high functioning in the classroom but struggle navigating the playground – which can be hard for anyone,” she said.

“A student might find themselves always on the outer of friend groups or being bullied for their differences.

“Finally, students on the spectrum usually have special interests and passions, so when designing tasks teachers should use these to full advantage.

Embracing strengths and supporting challenges

McLennan said an increase in awareness and acceptance has led to more positive mindsets throughout the community.

“In the first instance, look to school leaders, such as heads of inclusion and heads of special education, and teacher aides as they have a lot of expertise in supporting students on the spectrum.

McLennan said teachers and teacher aides are fantastic role models who celebrate and open conversations about diversity.

“I don’t ever see a teacher who thinks it is a burden to have a student on the spectrum in their class.

“Rather, they are thinking strategically about embracing student strengths and supporting student challenges – because that will result in the best possible learning outcomes.

“Teachers shouldn’t feel alone when working with students on the spectrum, there’s a lot of support both within and outside of schools to draw on.

“It’s very important – especially for early career teachers – to seek support, ask questions and go to professional development.

“Above all, strategies need to be centred on the student and talking with the student and their family is crucial to creating successful learning environments.”

References:

https://autismqld.com.au/page/what-is-autism