Quest for long service leave

A right to Long Service Leave was again a long quest. It wasn’t until 1964 when it was gazetted as an industrial provision across the Queensland workforce (13 weeks after 15 years) that employees in our sector actually had a right to long service leave.

In 1979, there are records of a consideration of establishing long service leave portability. In 1980 there was still comment being made on portability being an industrial priority.

It wasn’t until member action was taken that long service leave of 13 weeks after 10 years was achieved. It took the action of 28 members (28 members of the Toowoomba Grammar School in 1979) who voted 27 – 1 to withdraw support from voluntary and honorary extra-curricular activity on the forthcoming Saturday to convince the Headmaster and Board of Trustees that maybe they should have long service leave of 13 weeks after 10 years. Slow progress however, from there.

In 1981 the Ipswich Grammar School decided to get on board; June 1981 Downlands College was the first Catholic school to do so. Those officers who deal with long service leave calculations will be able to tell you chapter and verse the significance of the date 1986 in terms of actually having that accrual at 1.3 weeks for each year of service as this was the operational date for Catholic Diocesan schools.

Early childhood

Early childhood education employees have been part of our union since 1980 when the Queensland Kindergarten Teachers’ Association amalgamated with the then QATIS.

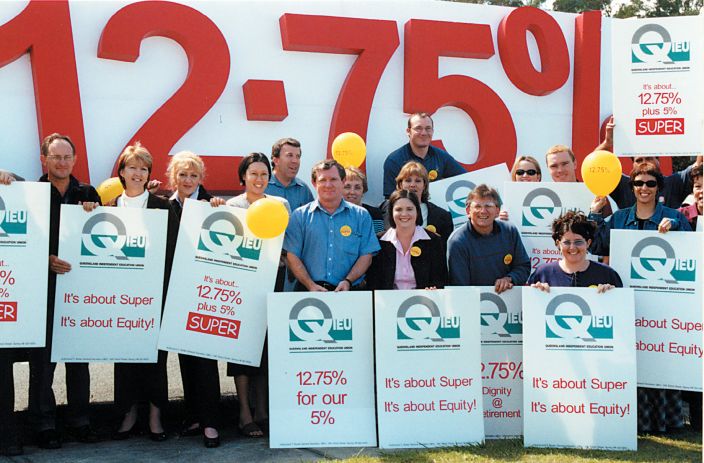

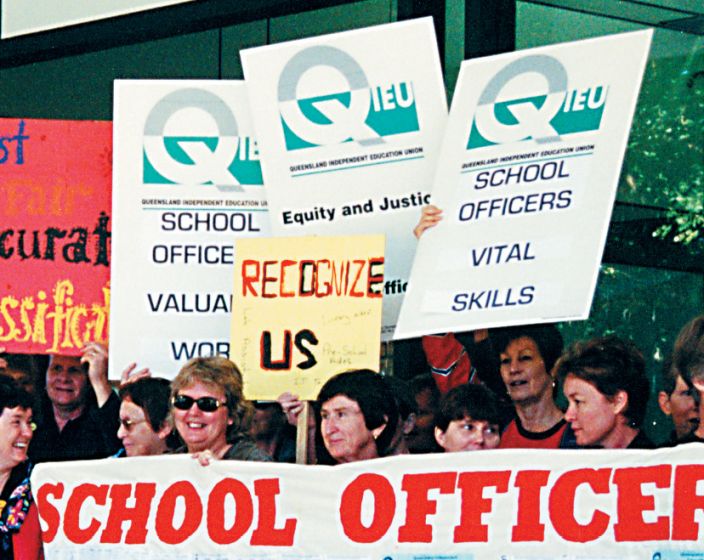

Our union has taken a significant role regarding equity issues. Issues of international engagement with regard to poverty, peace, education and so on have drawn our energies into a critical role of pursuing equity and justice in the community. In particular we campaign to improve the status of women.

It will come as no surprise to you that the Assistant Mistresses’ Association continually argued a claim for equal pay along with the Assistant Masters, often with conjoint submissions to the Commission for parity wage rates with the public sector. In those submissions they have made comments over the years on the right of teachers in independent schools to salaries equivalent with the public sector. Note the language: ‘the right’ - not ‘the pursuit of’ but ‘the right’ - to salaries equivalent to the public sector.

Maternity leave

In 1979 there was no maternity leave; not even a provision to take unpaid leave and there was certainly no concept of childcare facilities nor of carers’ leave. There was no equality of superannuation opportunity and concepts of equality in employment opportunity were very, very distant.

The issue of maternity leave (or accouchement leave as the term was) deserves further comment. In 1977, two years before the formation of the Working Rights of Women Committee, there is a comment in our records regarding the status of accouchement leave. Members were advised that there was no right to accouchement leave.

Accouchement leave existed in the public sector by regulation. A public sector regulation was clearly peculiar to the public sector and would require an Industrial Relations Commission decision if it were to apply in the private sector. So while it existed in the public sector it did not exist in the non-government sector where those public service regulations had no application.

The record goes on to say that although Catholic employers provided accouchement leave the principal could decide whether to keep the position open or not. So a woman might get accouchement leave but it didn’t necessarily mean that she could have her job back and it certainly didn’t mean that she necessarily got the same job back.

The record goes on to say that if she was not re-engaged within 12 months then she lost continuity of service because that was an Award provision. So unless the woman returned within 12 months all of her accruals would just disappear.

The union article of 1977 goes on to say this, “The second hard fact is that in the school organisation the expectant or nursing mother is a nuisance”. And there is more, “We can see their [the employer’s] point of view. It could prove difficult to find a registered teacher who is able to and willing to take your place for three months or so and some principals have it that a mother whose child is ill will be so unprofessional as to prefer to stay at home to nurse her sick child”.

These are comments of 1977 and it is no surprise that the Working Rights of Women Committee from its formation in 1979 well and truly livened up our understanding as a union in terms of gender issues.

It is fundamentally important to recognise that while we are a professional body we are also legitimately and distinctively a union: we are a profession; we are a union; one and the same. Employers and governments may attempt to frustrate the pursuit of legitimate aspirations of our profession and of our union of employees but they will be at best successful only in the short term. In the long term, those attempts are doomed to failure because at the end of the day we can say to employers and government over the ages, “We are union and we’re here to stay!”