Highly skilled educators are critical for high quality early childhood education (ECE). Yet there are widespread concerns that workforce preparation is inadequate and that the longstanding problem of educator shortages has not abated, researchers write.

The present shortfall of appropriately qualified educators is expected to escalate with growing demand for ECE (Intergovernmental Support Team, 2020). A group of researchers in early childhood education writes that evidence generated by their Exemplary Early Childhood Educators at Work (ECE@W) study can contribute to solving these issues.

The study investigated the complexity of ECE work by researching what early childhood educators do, what informs their work, and how workplaces support exemplary care and education of young children.

The research team examined what exemplary educators do across different qualifications: Certificate III, diploma and degree; and across positions: director, teacher, room leader and assistant.

Conceptual underpinnings

The ECE@W study was conceptualised using the Theory of Practice Architectures (Kemmis & Grootenboer, 2008). This theory considers both the conditions in work environments that inform educators’ dispositions, actions and abilities, and the individual agency of educators, stressing their capacity to problem solve and make wise decisions.

Methods

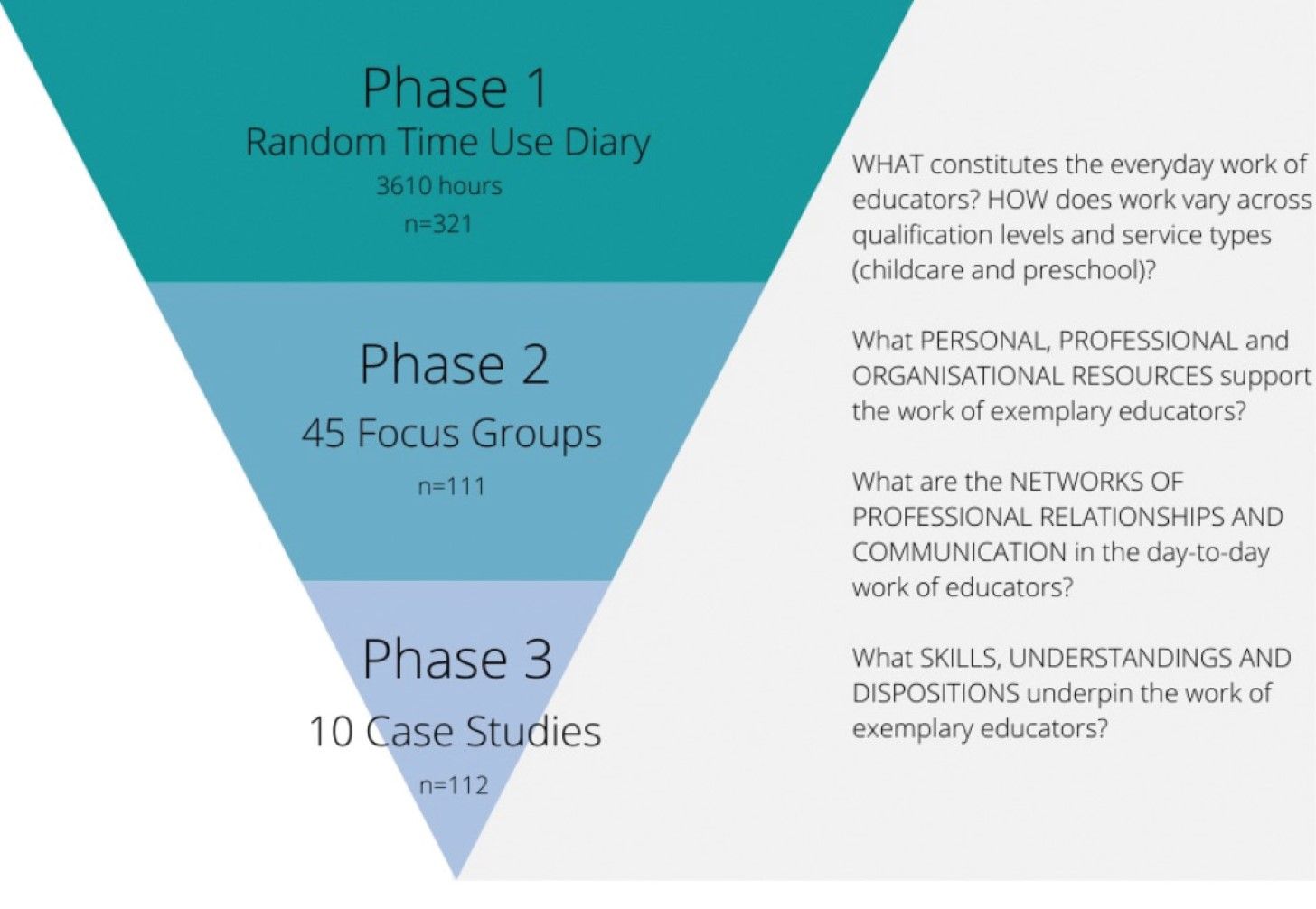

The project recruited educators in centres rated as Exceeding the National Quality Standard on all standards and elements, to participate in each of the three phases of data collection.

In Phase 1, we developed a taxonomy of 10 categories of ECE work to construct a Random Time Sampling Time Use Diary, delivered via a smartphone app (Wong, et al. 2022).

Educators reported what work activities they did, where they were, who they were with, and rated how they felt about their work experience during the previous hour. They did this for two randomly selected hours over 10 working days.

In Phase 2, we held focus groups with educators in the same job positions about what shapes and informs their practices and decision making.

In Phase 3, we shadowed individual exemplary educators, made observations of them as they worked, and together, reflected on selected vignettes of their practice.

Findings

Phase 1

Key findings from our analyses of 3610 hours of time-use diary records were:

- rapid changes of work activity within each six-minute reporting period

- multi-tasking as a normal characteristic of educators’ work

- low levels of stress and at the same time high levels of job satisfaction.

Phase 2

Our analyses of the personal, professional and organisational resources that support exemplary educators showed that: