IEU journalist Emily Campbell explores the findings of a recent study which found a specially designed video game helped preschool-aged children to experience and develop empathy.

Video games and their effect on children’s growth and development is a polarising topic, which has been subject to much debate in recent years as our world relies increasingly on digital technology.

Critics of video games are concerned the impact of increased screen time on young children can inhibit their social-emotional development, lead to increased aggression and promote anti-social behaviour.

However, the research team in a promising new study believe this is not necessarily the case, arguing “the solution is embedded in the problem when hybrid learning design blends real-life social interpersonal interactions with digital representations”.

The Empathy World: a game to cultivate empathic perception

The Empathy World was designed and created by Ling Wu, an early childhood education teacher and Research Fellow at Monash University, along with colleagues Dr Minkang Kin and Professor Lina Markauskaite from The University of Sydney.

With a keen interest in child development and young children’s social-emotional learning, specifically empathy, Ling decided to pursue this project as part of her PhD studies.

The trio of researchers used a bold and somewhat paradoxical approach to see how they could use technology to address the very issues technology is said to worsen.

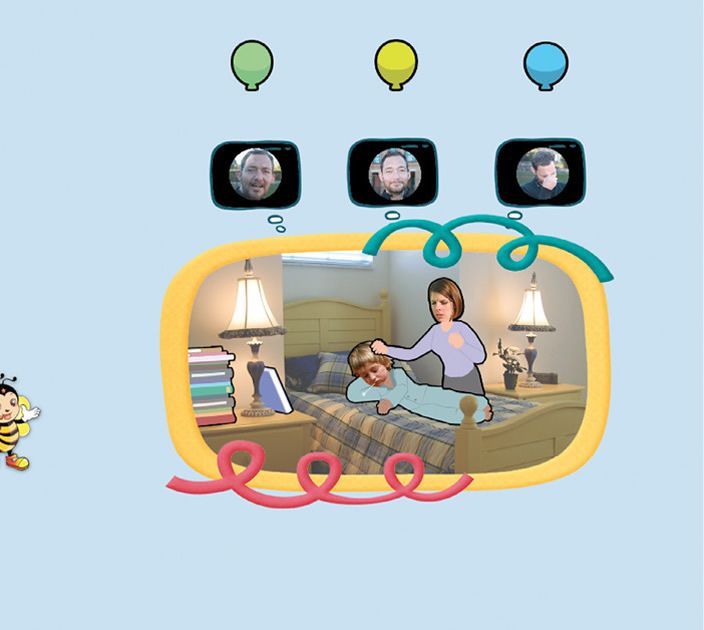

Using theory-informed design principles backed by extensive research, the group created The Empathy World, a tablet game which aims to promote empathic perception in preschool-aged children, which the researchers describe as “an essential building block for the ability to see, sense and understand the internal states of other humans” (Wu, Kim & Markauskaite, 2020).

As part of the study, 12 preschool students played The Empathy World regularly during their time at preschool over a period of three months.

The results are very promising, with the researchers finding that children who played The Empathy World were better able to pay attention to other people’s feelings and direct selective attention towards making appropriate decisions by selecting empathy worthy social cues with increased efficiency.

The research team found a positive relation between playing the game and enhanced empathic perception, supported by a brain imaging study which showed enhanced empathic sensitivity to harmful social interactions and increased attention to others’ feelings based on teachers’ observations.

Playing the game

During play Ling said children were exposed to a variety of interactive social scenarios referred to as ‘stories,’ with progressively more complex emotions and contexts for each story.

“Each scene in a story presents questions that prompt players to perceive social cues, perceive and understand emotions and perceive and analyse other perspectives in the context and engage in social-causal reasoning,” Ling said.

“For example, early in the game there is a scene in a sand pit with two babies playing together, where baby A is throwing a shovel at baby B and baby B is crying.

“The child playing can contextualise the story, seeing that sadness occurred when the baby was hurt, then extend their learning to understand it’s unkind to hurt others because the baby who was injured now feels sad,” Ling said.